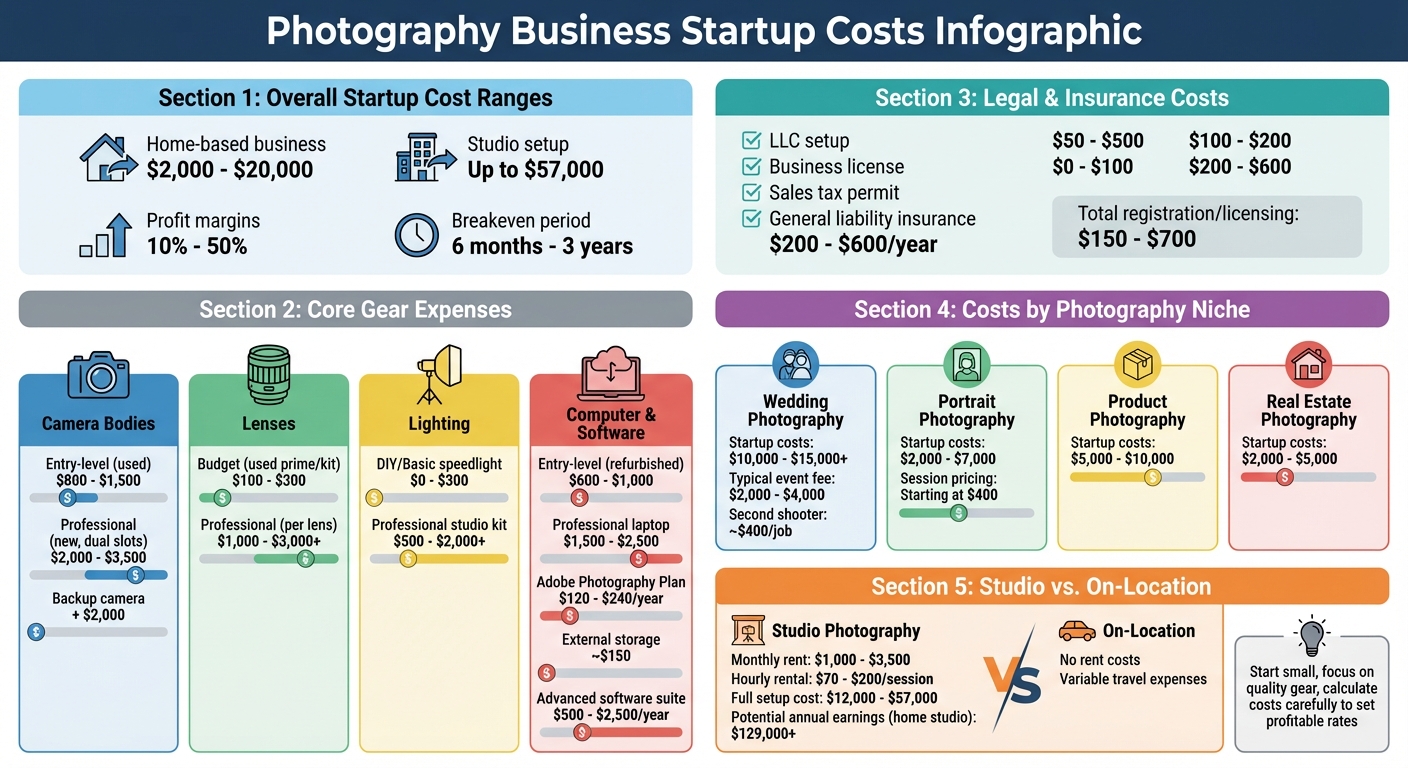

Starting a photography business in the U.S.? Here’s what you need to know about costs:

- Startup Costs: Home-based businesses range from $2,000 to $20,000; studio setups can climb to $57,000.

- Gear Expenses: Cameras cost $700 to $6,500, lenses $1,000 to $3,000 each, and lighting setups $300 to $2,000+.

- Software & Editing: Adobe subscriptions run $120–$240/year, with computers costing $600–$2,500.

- Legal & Insurance: LLCs cost $50–$500 to set up, with liability insurance ranging $200–$600 annually.

- Niche-Specific Costs: Wedding photography requires $10,000–$15,000+, while portrait photography starts at $2,000–$5,000.

Profit Margins: Expect 10%–50%, with a breakeven period of 6 months to 3 years. Your pricing should cover all expenses and reflect your niche. For example, wedding photographers may charge $2,000–$4,000 per event, while portrait sessions might start at $400.

Key Takeaway: Start small, focus on quality gear, and plan for expenses like licenses, insurance, and editing tools. Calculate your costs carefully to set profitable rates and grow sustainably.

Photography Business Startup Costs Breakdown by Category and Niche

Starting a Photography Business for $1,000

Photography Gear Costs

When it comes to photography, your camera and lenses will likely be your biggest expenses. To save money, consider buying quality used equipment. A good starting point is one dependable camera body paired with two versatile lenses. You can always expand your collection as your income grows. Professional lenses often range from $1,000 to $3,000 each, but you can find used prime or kit lenses for as little as $100 to $300. If you’re debating whether to upgrade your camera body or invest in better lenses, go for the lenses. They typically make a bigger difference in image quality and tend to retain their value over time.

Another smart way to manage costs is by renting specialized equipment, like macro lenses or drones, before deciding to buy. Don’t forget to budget for an editing setup. External hard drives will cost around $150, and Adobe's Photography Plan (which includes Lightroom and Photoshop) runs between $120 and $240 annually. Now, let’s dive into the specifics of cameras, lenses, lighting, and editing systems.

Camera, Lens, and Lighting Costs

A professional camera body with dual card slots - a must for preventing data loss - typically costs $2,000 to $3,500 new, or you can find used options for $800 to $1,500. For wedding and event photographers, having a backup camera body is critical, which could add another $2,000 or more to your expenses. Most professionals eventually invest in a "trinity" of lenses: wide-angle, standard zoom, and telephoto. Each of these lenses usually costs $1,000 or more.

Lighting needs will vary depending on your photography style. Portrait and studio photographers often require multi-light setups with modifiers, which can cost between $500 and $2,000. On-location photographers might start with a single speedlight for about $300+. To save money, you can use natural light and DIY reflectors made from inexpensive materials like white poster boards. Essential accessories like tripods range from $14 for basic aluminum models to $200–$1,600 for high-end carbon fiber options.

While cameras and lenses are the heart of your gear, a reliable editing system is just as important for producing professional-quality work.

Computer and Software Costs

Your editing computer needs to be powerful enough to handle large RAW files efficiently. High-end laptops typically cost $1,500 to $2,500, but refurbished models with sufficient RAM and GPU capabilities are available for $600 to $1,000. Plan to spend about $150 on external storage (for 2TB to 6TB hard drives), $120 to $240 per year for cloud backup services, and $120 annually for Adobe’s Photography Plan. If you’re looking for additional tools like AI editing software or studio management apps, your total software expenses could range from $500 to $2,500 annually. For those who prefer to avoid subscriptions, programs like Luminar offer lifetime licenses for about $79.

Entry-Level vs. Professional Gear Comparison

| Item | Entry-Level / Budget Kit | Professional / Industry Standard |

|---|---|---|

| Camera Body | $800–$1,500 (used DSLR/mirrorless) | $2,000–$3,500 (new full-frame with dual slots) |

| Lenses | $100–$300 (used prime or kit lenses) | $1,000–$3,000+ per lens (f/2.8 zooms, weather-sealed) |

| Lighting | $0–$300 (DIY reflectors or speedlight) | $500–$2,000 (studio kits with modifiers) |

| Computer | $600–$1,000 (refurbished or mid-tier) | $1,500–$2,500 (MacBook Pro or Dell XPS) |

| Software | $0–$120/year (free or basic Adobe) | $500–$2,500/year (Adobe CC + advanced tools) |

Starting with budget-friendly gear, you can keep your initial investment between $2,000 and $5,000, while a professional setup can easily climb above $10,000 to $20,000. Focus your spending on high-quality cameras and lenses, and look for affordable solutions for other essentials.

Licenses and Legal Requirements

Before booking clients, it's crucial to handle all necessary legal steps. These requirements are generally straightforward and come at a reasonable cost. Start by selecting a business structure - either a Sole Proprietorship or an LLC. A sole proprietorship is free to establish (aside from any local permits), but it leaves you personally responsible for business debts or lawsuits. On the other hand, setting up an LLC involves state filing fees ranging from $50 to $500, but it offers protection for your personal assets.

You'll also need a free EIN (Employer Identification Number) and, if you're operating under a name other than your own, a DBA (Doing Business As) registration. Check with your local city clerk's office or a Small Business Development Center to confirm if you need additional permits, such as a Home Occupation Permit for running a studio from home. Be sure to review local licensing fees, insurance needs, and business structure options to finalize your setup.

Business License and Registration Fees

Most areas require a general business license to operate legally, with fees typically ranging from $100 to $200. If you're selling physical products like prints or albums, you'll also need a sales tax permit to collect and remit state sales tax. The cost for this permit varies by state, ranging from free to about $100. Additionally, specialized permits may be necessary - for instance, FAA Part 107 certification for drone photography. In total, plan to spend approximately $150 to $700 for initial registration and licensing, depending on your location and business structure.

Once your licenses are in place, the next step is securing proper insurance to protect your business.

Insurance Fees

Insurance is a must-have for any photography business. General liability insurance covers you in case a client is injured during a shoot or if you accidentally damage property. Expect to pay between $200 and $600 annually for this type of coverage. Many photographers also opt for equipment insurance to safeguard against theft or damage to their gear. As Christopher Lin from SLR Lounge explains:

"One accident or equipment loss can cost more than your annual premium."

Some professional organizations, like the Professional Photographers of America (PPA), include insurance as part of their membership benefits, which can be a cost-effective option.

Sole Proprietorship vs. LLC Setup

Here’s a quick comparison to help you decide between a Sole Proprietorship and an LLC:

| Feature | Sole Proprietorship | Limited Liability Company (LLC) |

|---|---|---|

| Setup Cost | $0 (plus local license fees) | $50–$500 state filing fee |

| Liability Protection | No personal asset protection | Shields personal assets from business debts |

| Tax Filing | Included in personal tax return (Schedule C) | Pass-through taxation; can elect S-Corp status |

| Annual Requirements | Minimal; local renewals only | Annual reports and registered agent fees |

| Best For | Part-time or low-risk ventures | Full-time operations or high-liability exposure |

After deciding on your structure, open a dedicated business bank account to keep personal and business finances separate. This step is essential for maintaining the liability protections of an LLC and simplifies tax reporting. For added peace of mind, consult a local attorney or accountant to ensure you’ve chosen the right setup. Investing in professional advice now can help you avoid costly legal issues later. These preparations will keep your legal and financial matters organized as you grow your photography business.

sbb-itb-08dd11e

Costs by Photography Niche

The initial costs of starting a photography business can vary widely depending on the niche you choose. For instance, wedding photographers typically need to invest between $10,000 and $15,000. This covers essential equipment like backup cameras, professional lenses (such as 35mm, 50mm, and 70-200mm), and additional lighting gear. Portrait photographers, on the other hand, can get started with a smaller budget of $2,000 to $5,000, focusing on a camera body, one or two prime lenses (like a 50mm or 85mm), and basic reflectors. Somewhere in the middle, product photography requires an investment of $5,000 to $10,000, as it often involves specialized macro lenses and professional strobes.

Your choice between on-location work and studio photography also plays a big role in determining your expenses. On-location photographers avoid ongoing rent but need to budget for travel-related costs like fuel and parking. Studio photographers, meanwhile, face monthly rent ranging from $1,000 to $3,500, plus utilities and setup expenses. Many newcomers opt to rent studio space hourly, paying $70 to $200 per session, until they build a client base that justifies a permanent location.

On-Location vs. Studio Costs

If you choose on-location photography, you sidestep rent and utility bills by working at client venues or outdoor locations. However, you'll need to account for travel expenses, including fuel, parking fees, and vehicle wear and tear. Many photographers include travel fees in their pricing for jobs beyond a certain radius.

Studio photography, on the other hand, requires a larger upfront investment and ongoing fixed costs. Studio rent alone can range from $1,000 to $3,500 per month, and setting up a professional space involves additional expenses for lighting systems ($2,000 to $5,000), backdrop installations, and climate control. The total cost to establish a studio can fall anywhere between $12,000 and $57,000. Despite these costs, studio photography offers advantages like full control over lighting, a professional environment for client meetings, and the ability to shoot regardless of weather. For those who set up home studios, the savings on commercial rent can lead to annual earnings exceeding $129,000.

Wedding, Product, and Portrait Photography Costs

| Niche | Gear Startup Costs | Location Requirements | Additional Expenses |

|---|---|---|---|

| Wedding | $10,000–$15,000+ | On-location (venues) | Second shooter fees (~$400 per job), backup equipment, client gifts, travel costs |

| Portrait | $2,000–$7,000 | Home studio, on-location, or rented space | Backdrop systems, props, client gallery software |

| Product | $5,000–$10,000 | Dedicated studio space | Macro lenses (e.g., 100mm f/2.8), strobes, light tents, styling props |

| Real Estate | $2,000–$5,000 | On-location (homes) | Wide-angle lens (16–35mm), tripod, drone permits/licensing, high vehicle mileage |

When selecting your niche, consider both your budget and the market demand. Portrait photography is a great starting point for beginners, as it has a relatively low cost of entry and steady demand. Wedding photography, while lucrative with event fees often exceeding $2,000, requires a considerable upfront investment. Real estate photography offers consistent work in active housing markets but demands specialized equipment like wide-angle lenses and drones. If you can operate out of a home studio, you'll retain more of your earnings compared to renting commercial space. Knowing these niche-specific expenses helps you plan your pricing and profits effectively.

Profit Margins and Breakeven Analysis

When running a photography business, understanding your revenue per session and breakeven point is crucial for staying financially stable. Profit margins in the photography industry generally range from 10% to 50%, with the average sitting around 50%. To maintain a thriving business, you need to calculate your own Cost of Doing Business (CODB) and set prices that reflect your expenses and desired profit. Let’s dive into how to analyze your costs and determine profitable rates.

Cost Analysis and Pricing Methods

Your CODB includes all business expenses, and calculating it accurately is the foundation for setting the right prices. The formula looks like this: (Total Annual Overall Expenses + Desired Salary) / Number of Billable Days. For instance, if your yearly expenses total $30,000, you aim for a $50,000 salary, and you anticipate booking 80 shoots annually, your minimum rate per shoot would be $1,000. According to Jeff Guyer, CODB not only accounts for expenses but also helps evaluate the potential success of each project.

When pricing, keep in mind the difference between fixed costs and variable costs. Fixed costs, such as studio rent, insurance, and software subscriptions, typically range from $500 to $2,500 annually and remain constant regardless of your workload. Variable costs, on the other hand, include travel expenses, equipment rentals, and assistant fees, which vary with each job. Many photographers apply a 2.85x markup on physical products like prints and albums to cover both material costs and labor. In competitive markets, an 8-hour day is often valued at $1,200.

Revenue Projections and Breakeven Formulas

Knowing your breakeven point - the number of sessions you need to book to cover your costs - is key to running a profitable business. To calculate it, divide your total fixed costs by your contribution margin. The contribution margin is the revenue per session minus the variable costs for that session. For example, if your fixed monthly costs are $3,000, and each session earns $400 with $100 in variable costs, your contribution margin is $300. You’d need to book 10 sessions per month to break even ($3,000 ÷ $300 = 10).

Revenue potential varies depending on your niche and pricing strategy. Home-based photographers often earn over $129,000 annually, while hourly rates range from $25 to $75 for beginners and $75 to $500+ for seasoned professionals. Most photography businesses reach their breakeven point within 6 months to 3 years of starting. Tools like IdeaFloat’s Cost Analysis and Financial Projections can help you track your income and expenses, offering a clear view of when your business will turn a profit.

Low-End vs. High-End Profit Scenarios

To illustrate how pricing and session volume affect profitability, consider the following examples:

| Scenario | Monthly Sessions | Price/Session | Monthly Revenue | Monthly Expenses | Net Profit | Annual Profit |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low-End Portrait | 15 | $400 | $6,000 | $4,200 | $1,800 | $21,600 |

| Mid-Range Wedding | 4 | $2,500 | $10,000 | $5,500 | $4,500 | $54,000 |

| High-End Commercial | 3 | $5,000 | $15,000 | $6,800 | $8,200 | $98,400 |

| Premium Wedding | 6 | $4,000 | $24,000 | $9,200 | $14,800 | $177,600 |

The takeaway? Time is money. Every hour spent on pre-production, shooting, editing, and client communication needs to be factored into your pricing. Alexa Klorman, owner of Alexa Drew Photography, sums it up perfectly:

"I have my price, and I'm pretty strict about sticking to it because it's a fair price. Because I'm transparent with what my packages cost, generally when people contact me, they're ready to book".

Conclusion

Starting a photography business requires a well-thought-out plan that balances costs and potential revenue. The initial investment can vary widely depending on your business model, whether you're operating a small home-based studio or a full-scale commercial venture. The key is to develop a streamlined, profitable plan that aims to break even within 6 months to 3 years.

Once you've covered startup expenses and legal requirements, refining your overall strategy becomes essential. Pricing plays a major role and often depends on your niche. Specializing allows you to target specific markets and set competitive rates. As Alexa Klorman of Alexa Drew Photography explains:

"As my business grew and as I started to get more clients and increase my price, I wanted to make sure that the quality of my photos was validated in what I was charging".

To ensure your pricing aligns with market demand, calculate your Cost of Doing Business (CODB) accurately. Separate personal and business finances early, and set aside 30%-40% of your revenue for taxes. For equipment upkeep, allocate 10%-15% of your initial investment annually for maintenance and upgrades. Keep in mind that photography profit margins typically range between 10% and 50%.

These financial steps build on earlier discussions about startup costs and niche selection. Before committing significant funds to equipment or legal structures, validate your business idea using reliable market data. Tools like IdeaFloat's Problem Validator, Market Sizing, and Financial Projections can help you assess demand, identify underserved niches, and forecast potential revenue. While the U.S. photography industry is expected to reach $16 billion in 2024-2025, success hinges on entering the market with a data-driven plan, not just a love for photography.

Start lean, price smart, and let the numbers guide your decisions. Focus on building a sustainable business model - not just acquiring the latest gear.

FAQs

What are the main differences in startup costs between running a photography business from home and operating a studio?

Starting a photography business from home is often a more budget-friendly option, with initial costs ranging from $2,000 to $20,000. This budget typically covers the essentials: a camera, lenses, lighting, a computer, editing software, business registration, and basic insurance. Since you're working out of your own space, you avoid additional expenses like rent or property leases.

On the other hand, setting up a studio comes with a heftier price tag. Studio startup costs usually fall between $12,000 and $57,000 or more, as they include leasing or purchasing a physical location, utilities, professional lighting, backdrops, and other specialized equipment. Additionally, running a studio means handling monthly overhead expenses like rent (often $1,000 or more), utilities, and higher insurance costs, making it essential to carefully manage cash flow.

The main distinction lies in the financial focus: home-based setups prioritize gear and licensing, while studio operations demand substantial investment in space and infrastructure, resulting in higher ongoing expenses.

How can I manage and reduce gear costs when starting a photography business?

To keep your gear expenses in check, focus on the basics that will cover most of your shooting needs. Start with a reliable full-frame or APS-C camera, a versatile prime lens like a 50mm f/1.8, and a simple lighting setup. If you're looking to save money, consider purchasing used equipment from trusted sources - this can help you cut costs without sacrificing quality.

For pricier items that you’ll only use occasionally, like specialty lenses or advanced studio lighting, renting can be a smart alternative. Many local camera shops and manufacturers offer affordable rental options, giving you access to high-end gear without the need for a large upfront investment.

Set a realistic budget - say, under $10,000 - and prioritize multipurpose tools, such as zoom lenses that can handle both wide-angle and telephoto shots. Steer clear of splurging on unnecessary extras and build your kit gradually as your business grows. With thoughtful planning, you can keep costs low while still delivering top-notch results.

What legal steps and insurance should I focus on when starting a photography business?

When launching a photography business in the U.S., the first step is deciding on a business structure. Common options include a sole proprietorship or an LLC. This choice impacts how you'll handle taxes and the level of legal protection you'll have. Next, you'll need to register your business name (DBA) with your state, apply for an Employer Identification Number (EIN) through the IRS, and, if you're selling prints or services, secure a state sales tax permit. Don't forget to stay on top of federal and state income taxes, as well as self-employment taxes on your earnings.

Insurance is another critical piece of the puzzle. A general liability policy can cover incidents like a client tripping over your gear, while professional liability insurance offers protection if a client claims dissatisfaction with your work or missed deadlines. To safeguard your equipment, consider equipment insurance to cover theft, loss, or damage. If you're planning to hire employees, you might also need workers' compensation insurance, depending on your state's requirements. These insurance policies are key to shielding your business from potential risks.

Related Blog Posts

Get the newest tips and tricks of starting your business!